"Unofficial" - 35C3 CTF

by holocircuit

Unofficial was a cryptography challenge from 35C3 CTF, involving modular arithmetic.

It had an unintended easy solution which worked with versions of Sage older than 8.3 (see below). I still haven’t heard anyone describe why that solution worked - let me know if you know how!

The challenge

We’re given a file server.py, and a PCAP file. Here’s the server file:

import os, math, sys, binascii

from secrets import key, flag

from hashlib import sha256

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

p = 21652247421304131782679331804390761485569

bits = 128

N = 40

def rand():

return int.from_bytes(os.urandom(bits // 8), 'little')

def keygen():

return [rand() for _ in range(N)]

if __name__ == '__main__':

# key = keygen() # generated once & stored in secrets.py

challenge = keygen()

print(' '.join(map(str, challenge)))

response = int(input())

if response != sum(x*y%p for x, y in zip(challenge, key)):

print('ACCESS DENIED')

exit(1)

print('ACCESS GRANTED')

cipher = AES.new(

sha256(' '.join(map(str, key)).encode('utf-8')).digest(),

AES.MODE_CFB,

b'\0'*16)

print(binascii.hexlify(cipher.encrypt(flag)).decode('utf-8'))

Writing this down in symbols, the server has a key of 128-bit values (which is private), and a value , which is 134 bits long.

It issues a challenge of 128-bit values, and expects a response given by .

If the response is correct, it gives us the flag, AES-CFB encrypted with the SHA256 of the key. So recovering the key is enough to get the flag.

We can extract out the streams from the PCAP file using tcpflow -r surveillance.pcap. The PCAP file contains 40 challenge/response pairs: 39 of them are valid, one isn’t.

If we try and factorise we’ll see it isn’t prime - it’s a square with a bunch of small factors. See FactorDB for the full factorisation - it turns out it won’t be that important for the challenge.

Part 1: Solving some simultaneous equations

Using the 39 valid solutions, we can write down some linear simultaneous equations for the key, modulo p. Each valid response gives us an equation for the key, given by

where is the challenge and is the correct response value.

Because we only have 39 equations, and 40 unknowns, we can’t solve for a single value of the key just based on this. Instead, we’ll get a family of solutions, which we can find with a method like Gaussian elimination. We end up getting a plane of solutions which look like

where we know and , and can take any value . Different values of will give different solutions.

One thing that complicates this slightly is that isn’t prime - and Gaussian elimination is only guaranteed to work for prime values. Luckily in the example we have here, Gaussian elimination still works, so we still get a family of solutions in the above form.

Code to do the Gaussian elimination is below. You’ll need to extract out the PCAP file into the data/ folder first.

import glob

import random

def egcd(a, b):

if a == 0:

return (b, 0, 1)

else:

g, y, x = egcd(b % a, a)

return (g, x - (b // a) * y, y)

def modinv(a, m):

g, x, y = egcd(a, m)

if g != 1:

raise Exception('modular inverse does not exist')

else:

return x % m

files = glob.glob("data/*01337")

data = []

p = 21652247421304131782679331804390761485569

for f in files:

with open(f) as fd:

response = int(fd.read().strip())

serverf = f.replace("data/", "").split("-")[1] + '-' + f.replace("data/","").split("-")[0]

with open("data/" + serverf) as fd:

params = [l.strip() for l in fd.readlines()]

challenge = list(map(int, params[0].split()))

if params[1] == "ACCESS GRANTED":

data.append([challenge, response])

# Rearrange data ready for Gaussian elimination!

l = []

for (coefficients, target) in data:

l.append(coefficients + [target])

def gaussian_elimination(m, NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS, NUMBER_OF_COEFFICIENTS):

assert len(m[0]) == NUMBER_OF_COEFFICIENTS + 1

assert len(m) == NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS

def reduce(target, source, factor):

m[target] = [(x - factor*y) % p for (x, y) in zip(m[target], m[source])]

def swap(target, source):

l = m[target]

m[target] = m[source]

m[source] = l

column = 0

while column < NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS:

if egcd(m[column][column], p)[0] != 1:

target = random.choice(range(column + 1, NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS))

print("uh oh. trying to swap with another... %d,%d" % (column, target))

swap(column, random.choice(range(column + 1, NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS)))

continue

for j in range(column + 1, NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS):

factor = m[j][column] * modinv(m[column][column], p)

reduce(j, column, factor)

column += 1

return m

def solve(equations):

NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS = len(equations)

NUMBER_OF_COEFFICIENTS = len(equations[0]) - 1

reduced = gaussian_elimination(equations[:], NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS, NUMBER_OF_COEFFICIENTS)

free_variables = NUMBER_OF_COEFFICIENTS - NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS

assert free_variables == 1 # just assuming this is so for simplicity

solution = ([None] * NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS) + [(0, 1)]

for coefficient in range(NUMBER_OF_EQUATIONS - 1, -1, -1):

row = reduced[coefficient]

# assert that we're reduced, i.e. in upper triangular form

if coefficient != 0:

assert set(row[:coefficient]) == set([0])

lhs = row[coefficient]

inverse = modinv(lhs, p)

rhs = (row[-1] % p, 0)

for other_coefficient in range(coefficient + 1, NUMBER_OF_COEFFICIENTS):

f = lambda i: rhs[i] - (row[other_coefficient] * solution[other_coefficient][i])

rhs = (f(0) % p, f(1) % p)

rhs = (rhs[0] * inverse % p, rhs[1] * inverse % p)

solution[coefficient] = rhs

a = map(lambda x : x[0], solution)

b = map(lambda x : x[1], solution)

# Try asserting that something is actually a solution

for k in range(200):

suggested_solution = [(a[i] + k*b[i]) % p for i in xrange(len(a))]

for eq in equations:

lhs = sum(suggested_solution[i] * eq[i] for i in range(NUMBER_OF_COEFFICIENTS))

rhs = eq[-1]

assert (lhs - rhs) % p == 0

return (a, b)

(a, b) = solve(l)

Part 2: Finding the unique key solution

OK, so we have different solutions for the key - how do we know which one is right?

One extra piece of information we have is that the key is only 128 bits long, compared to which is 134 bits long, and our solutions above are only guaranteed to be less than .

The probability of one of our key values being less than 128 bits long is about - over all 40 values, that’s , which is much smaller than ! So that should be enough to identify a unique key value.

How do we do this? We’ll use an algorithm called LLL - I’ll explain what it does, and then how we’ll use it.

Part 2a: What’s LLL?

LLL, or Lenstra-Lenstra-Lovász is an algorithm on lattices.

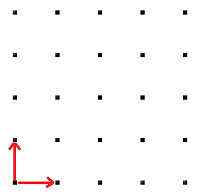

If we have a basis of vectors, the lattice generated by them is given by all integer combinations of the basis.

For example, if our basis is , then the lattice generated by them is the integer grid:

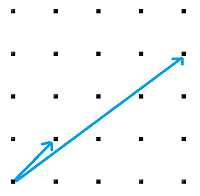

Now, there are a bunch of possible choices of basis that we could have for a lattice. For example, maybe we could have chosen instead:

This is exactly the same lattice, with a different basis. We can see it’s the same because we can generate from these:

and so those vectors are enough to generate the whole grid.

Now, LLL is an algorithm which takes in a basis for a lattice, and tries to find a different basis which is “nice”. Explaining what exactly LLL is aiming for is a little tricky, but being very hand-wavy, it tries to make sure that the new basis is as “small” as possible.

For example, if we give LLL the second basis above, it’ll try and produce something that looks more like the first one - because the vectors in the first example are smaller.

How does this matter for cryptography? With a bit of imagination, we can use this as a problem-solving technique. Let’s suppose we’re trying to find some secret value. If we can:

- come up with some lattice

- prove that value is in the lattice

- prove that value is “small” compared to the lattice

then we might be able to use LLL to find it! Let’s see an example.

Part 2b: Using LLL

So to summarise, from Part 1, we have integers , and we want to find an integer such that

Writing this differently, this means there are integers with

How can we represent this as a lattice? Let’s try something like the below, where the rows of this matrix will be the rows of our basis:

We expect the and to have around the same number of bits as , so the rows of this matrix all have size at least 134 bits.

Now, the following vector will be inside the lattice generated by this basis:

because it’s the sum of:

- 1 times the first row

- times the second row

- times the third row

- etc.

This vector is pretty small! The entries only have 128 bits, compared to what we started with which was 134 bits.

So we have a vector we want to find (because it contains the key!), which is in our lattice, and “small”, so maybe LLL can find it! There are two problems though:

- We have 42 vectors there, but our vectors are of dimension 40.

- We don’t want just any combination of the vectors - we want to make sure that it only picks one multiple of the first row.

We’ll fix this by adding in two extra columns to our vectors, like so:

The linear combination that we’re aiming for is therefore .

What should be?

For : we want to try and get LLL to only use 1 multiple of the first row. We’ll do this by setting it to something large, e.g. on the order of 128 bits. I chose . This will try and “persuade” LLL to not use too many multiples of this row.

For : we want this to be small. We don’t want to be much bigger than the rest of the vector, as it means this vector we’re aiming for is no longer small. LLL works fine with rational entries, so I chose to be . This means that should have around 128 bits, so it’s in line with the size of the other vectors.

After picking these, we can construct the matrix and apply LLL. We’ll look for a row where the second-last column is , and assume that row corresponds to the key.

The following code does so - I used SageMath to get a convenient implementation of LLL. This calculates the key, checks that it satisfies the constraint on the number of bits, and then prints out the decryption of the flag.

# (use code from above to get a, b)

from sage.all import *

import time

COUNT = len(a)

def fract_of_long(l): return fractions.Fraction(l, 1)

big = fract_of_long(2**128)

small = fractions.Fraction(1, 2**6)

rows = []

rows.append(map(fract_of_long, a) + [big, fract_of_long(0)])

rows.append(map(fract_of_long, b) + [fract_of_long(0), small])

for i in xrange(COUNT):

new_row = [fract_of_long(0)] * (COUNT + 2)

new_row[i] = fract_of_long(p)

rows.append(new_row)

M = matrix(rows)

print "[+] Calculated matrix, running LLL"

# I needed to pass in the arguments, otherwise I got a floating-point exception. Not sure why. I think this makes it use "exact" rationals.

N = M.LLL(fp="rr", algorithm="fpLLL:proved")

print "[+] Looking for row with 2^{128} or -2^{128} in the second-last column..."

for row in N:

if row[-2] == 2**128:

print "[+] Found the key!"

break

elif row[-2] == -1*(2**128):

print "[+] Found the key!"

row = [-1*x for x in row]

break

key = row[:-2]

# Assert that all entries of the key are only 128 bits long

for c in key:

assert c < 2 ** 128

from hashlib import sha256

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from binascii import unhexlify

actual_key = sha256(" ".join(map(str, key))).hexdigest()

print "[+] Key is %s" % actual_key

enc_flag = unhexlify("aef8c15e422dfb8443fc94aa9b5234383d8ee523d6da9c4875ccf0d2cf24b1c3fa234e90b9f9757862d242063dbd694806bc54582deddbcbcc")

cipher = AES.new(unhexlify(actual_key), AES.MODE_CFB, "\x00" * 16)

print cipher.decrypt(enc_flag)

Part 3: … or just use Sage 8.1

This challenge was unintentionally easier than expected. It turns out if you just plug the equations into Sage 8.1, it spits out the key. This is pretty surprising! There should be p many solutions - how come it just picks the right one? Interestingly, it doesn’t work with versions of Sage newer than 8.3 (the linear algebra solver version changed between these two versions).

I’m not sure exactly why this works, and haven’t yet heard a convincing explanation. Sage tries to pick a solution that’s “close” to the null space as it can, but I don’t understand precisely what it does.

If you understand the maths behind this, I’d love to know. Drop me a DM on Twitter.

tags: ctf - cryptography - mathematics